How can we comprehend sustainability in a context where that word does not exist?

How can we fashion contemporary architecture appropriate to people and place without modern construction materials?

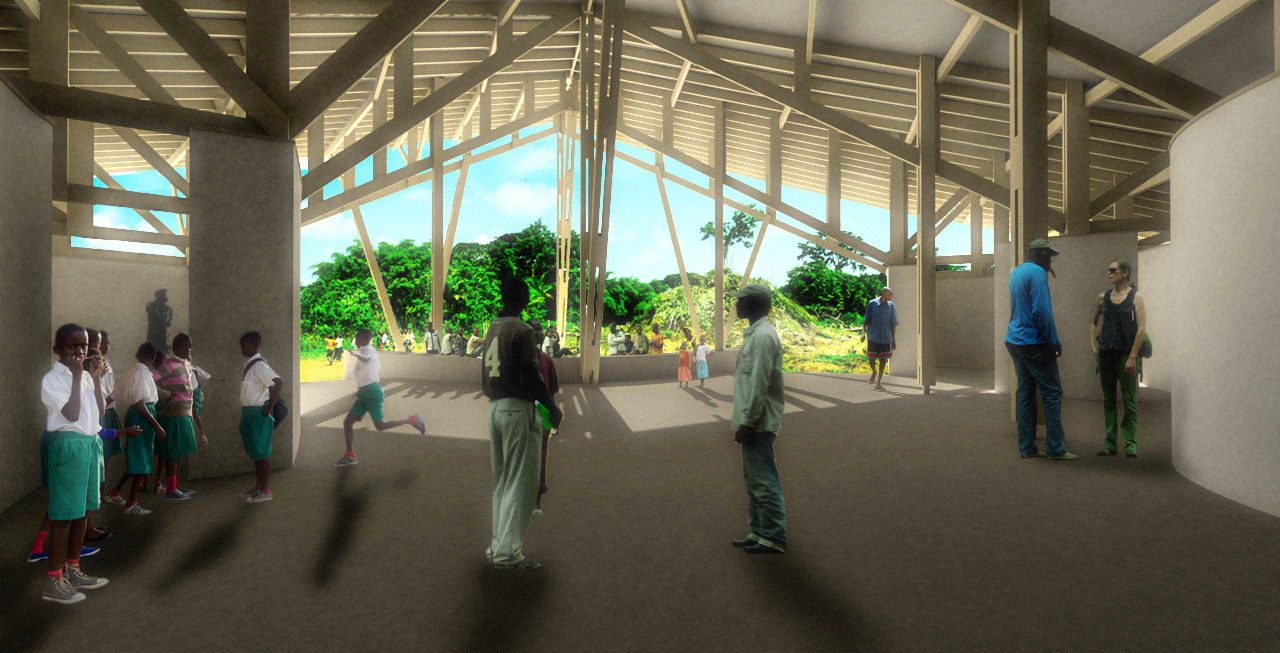

How can a school in the Congolese jungle teach its students and its entire community?

These are the sorts of questions I have had the opportunity to tackle at work lately, and for that I am grateful. The Africa Conservation School in Ilima, Democratic Republic of Congo is one piece of a longer-term partnership between the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) and MASS Design Group. Ilima is one of four schools AWF is currently constructing in support of their mission to promote conservation through community engagement. Through this project I have learned plenty about what it means to work in a resource limited context.

Designing a school in the DRC jungle is kind of like designing a school on the moon. All materials reach the job site by a month-long boat voyage on the Congo River followed by a seven-hour motorbike ride through the jungle. In such a remote context, emphasizing process and using locally available resources are by necessity the only ways to work. The priority shifts from designing things to designing for the behavior of people. The community is constructing the entire school, and we spent an incredible amount of time imagining the best way to explain how to build complex architecture to a community without any construction experience. With this task in hand, visual communication became an important but challenging part of our role as designers.

To understand the meaning of sustainability in a place like DRC is a real challenge. Self-sufficiency is a slippery idea we grappled with in choosing the material palette of the school. Specifically, the question of how to build the roof became a focal point of our conversation. To import a metal roof by motorcycle is not exactly viable, and on top of that, replacing one should it fail would be an insurmountable financial and logistical challenge for the community. In the end, we decided to adapt wood shingles – a technology with few, if any, precedents in the Congo – to the forested village context. This choice presented an interesting opportunity to teach the community – and ourselves – a new skillset that could provide economic opportunity and self-sufficiency. A wood roof might not last as long as a metal one, but if the community can repair it themselves, it will be a longer-term solution. In our view, this is a specific sustainability suited to the context.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fd5ChXRpiR4

Projects like Ilima are meaningful precisely because they impact an entire community in a tangible way. But what I also appreciate about this project is how much learning and enjoyment it brought to our project team. To teach someone how to make shingles, you have to teach yourself. Designing and learning with the goal of teaching others, well, that is exactly the kind work I want to be doing.

For progress on AWF Ilima School, follow #AndrewinIlima on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. For more info, learn about AWF’s conservation schools and stay up to speed on what MASS is doing these days.