Tonight was special because a controversial film on a topic that is considered by many to be too taboo to even utter, “homosexuality,” was to be screened right here in Lilongwe, the capital city of Malawi. The documentary film entitled “Umunthu” was contentious because it was setting in-motion a different kind of conversation on sexuality in southern Africa.

In attendance were dozens of locals and azungu (non-Malawians or white people) ranging from the US Ambassador to Malawi and the President’s Advisor for Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) to scores of young Malawians. They congregated, eagerly, to engage in a rare but sobering discussion on homosexuality.

But let me take a step back. You may be wondering, just as I did a year ago, where is Malawi?

Malawi is a small southern African country that removed its shackles from the British and gained independence 50 years ago. It is landlocked. It has a population of about 17 million people – of whom are mostly young and rural subsistence farmers. You may have heard about Madonna’s adopted children or the debilitating AIDS epidemic. However, Malawi is more than just poverty and sickness. Its gem is its people. Malawi is nicknamed the “Warm Heart of Africa.” Malawians are honest, compassionate, hard-working and God-loving, and they fervently want to see Malawi prosper. And this film, Umunthu, is a testament to this desire to get the spokes turning towards achieving progress.

What does it mean to be gay in Malawi?

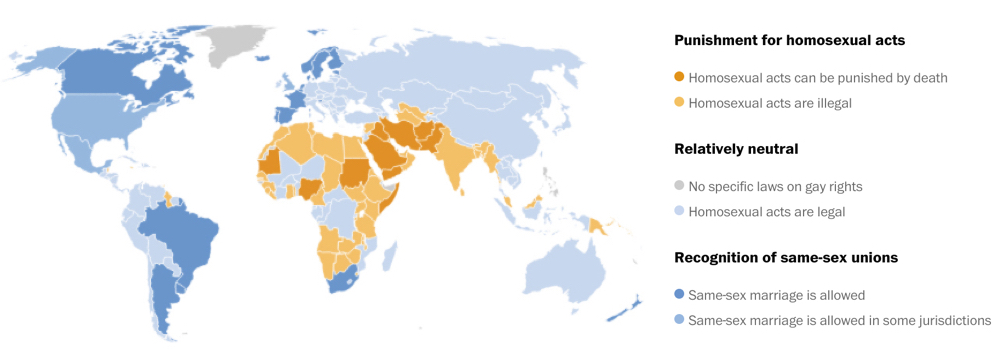

Being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex in Malawi is punishable by imprisonment. The Malawian Penal Code states that, “Carnal [relating to sexual] knowledge against the order of nature,” or “acts of gross indecency between males” and likewise, females, is a “felony and liable to imprisonment.” Unfortunately, this is the case in roughly 70 other countries around the world.

In late-2009, Malawi’s homosexuality law was thrust into the international spotlight when two Malawian men were arrested for holding a traditional “engagement” party. They were found guilty and charged with committing “unnatural offenses” and “indecent practices between males.” They were ordered to serve the maximum sentence of 14 years in prison. However, because of an international outcry the two men were pardoned and released.

In 2012, President, Joyce Banda, suspended the law — however, it remained only until 2014. Fierce resistance from churches and lobbying groups derailed its suspension, and the “anti-homosexuality law” was reinstated.

In March of this year, this issue surfaced on the front page of a leading Malawian newspaper. The Malawian government had applied for a grant totaling a half-million US dollars from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to combat HIV/AIDS among LGBTI persons. It seemed like the government would be softening its stance against homosexuality, but I was mistaken. In the interview, a Member of Parliament and Minister reiterated the government’s stance by saying, “It is still a crime to anyone engaging in the practice…There will be no change in laws on homosexuality.”

Can “Umunthu” pave a way for tolerance of the LGBTI community?

Umunthu is a film that was directed and produced by a young Malawian, Mwizalero Nyirenda, and supported by the Art and Global Health Centre Africa — a partner of US-based, Global Health Corps, which is a community of emerging global health leaders that I became a part of in July 2014.

According to the film’s director, the objective was not to serve as a mouthpiece, but rather as a platform to engage Malawians in an open discussion on homosexuality. One faith leader highlighted how religion and social norms do not accept same-sex relationships. Others mentioned how Malawi is still “religious” and “vastly rural and traditional.” One even charged homosexuality as being “not African.” However, one young person refuted that, “Societies and cultures evolve and adapt,” asserting that societies can embrace LGBTI peoples — as they did with women rights, feminism and Christianity.

Additionally, the US Ambassador to Malawi chimed in and likened the issue to a personal experience during Apartheid in South Africa when she dated her black South African boyfriend — her now husband. She offered a solemn message, “Homosexuality is not an LGBTI issue, but a human rights issue.”

In contrast, the President’s Advisor of NGOs in Malawi was more cautious. He acknowledged that homosexuality was still illegal, but said that he was proud to live in a “democracy where people can talk about it openly,” although he stopped short of any claims of a government repeal to the anti-homosexual law.

Umunthu was an appropriate title for a controversial film. The literal translation of umunthu is difficult to define, but its simple meaning is “humanity.” As an outsider, I cannot truly understand it, but it is a “way of life” shared across southern Africa. According to one Malawian in the film, “Umunthu means people can disagree with one another but at the end of the day still respect them.” It is a tradition that exemplifies love, compassion and mutual respect regardless of who they are, the tribe they are from, their nationality or religion.

Thus, by examining the issue of homosexuality through the lens of “Umunthu” can we set the stage for tolerance and equality for the LGBTI community in Malawi and elsewhere.

Coming OUT of the closet [again].

Everyday LGBTI people right here in Malawi and around the world are being forced to live discreetly in fear of alienation, humiliation and assault. I may be criticized for what follows, but I can no longer stand on the sidelines of injustice. I am gay. I have beat myself up countless times before because I felt ashamed, conflicted, and immoral — feelings that I now realize were unwarranted. I came out three years ago, but one year ago, I felt obliged to return to the “closet” because I was moving to a country where homosexuality is illegal. I feared for my personal safety and the prejudice that I would face.

After four months of living in Malawi, I decided to come out to my Malawian and African colleagues as I could no longer hide behind the lies. Since then — with their support —I have been emboldened and empowered to simply be “me.” Coming out in Malawi allowed me the opportunity to tell my story, and to show that regardless of my sexuality, I can be just as effective as any other person working in global health.

As my one-year fellowship comes to a close, I am more confident to stand up for universal social justice and health equity. These are not concepts that are philosophies of “the West,” but moral ideologies that all GHC fellows share, regardless of nationality. We have the responsibility, as young global leaders, to challenge one another and critically analyze the underpinnings of injustice and inequality.

Demystifying (de-taboo-ing) homosexuality through discourse and action.

Love is unconditional — not traditional, religious, racial or limited to which continent you live on.

Therefore, the discourse on homosexuality should not end here, so I call on you to have these discussions with your workmates, friends, spouses and families. Raise these uncomfortable questions. If you find yourself uneducated about the LGBTI community, then make yourself more informed. Only through knowledge and awareness can you dispel the myths and misconceptions surrounding homosexuality. My hope is that we all come together in solidarity against prejudice and hate, and truly embrace the quintessence of Umunthu.

*Mahalo to those who inspired me to write this blog: Aisha, Barbara, Julie, Perry, Tali, Orrin, Mervin, Natasha, Joe, Umba, Helen, David, Nohea, Jess, Carrie and the extended Global Health Corps ‘ohana.

Map: The Washington Post, The state of gay rights around the world, 2015