During the Article 25 Global Day of Action, a group of Ugandan-based Global Health Corps (GHC) fellows joined Uganda Development and Health Associates (UDHA) on the islands of Kaaza and Serinyabi in Mayuge District. These islands are located in Lake Victoria, and have no health facilities.

The series of events started the night of October 24th and were centered on a petition that the islanders were signing to demand that the government recognize their right to health.

Sam Agona and Heather Zimmerman, fellows at the UDHA placement, sent out an email asking other GHC fellows to join the “island communities to highlight their lack of access to appropriate health care services and demanding the government recognize their right to health with construction of health centres on the islands.”

Kasese (where my co-fellow and I live) to Iganga (where Sam and Heather live) is about 11-12 hours’ travel, but we wanted to be there for this kind of advocacy.

One of the scheduled activities was free HIV Testing and Counselling to people on the island. As I am not qualified to test nor counsel but could speak the local language, I (wo)manned the registration. It was at this desk that I struggled and reflected on the divide between the informal and formal during our learning and unlearning process.

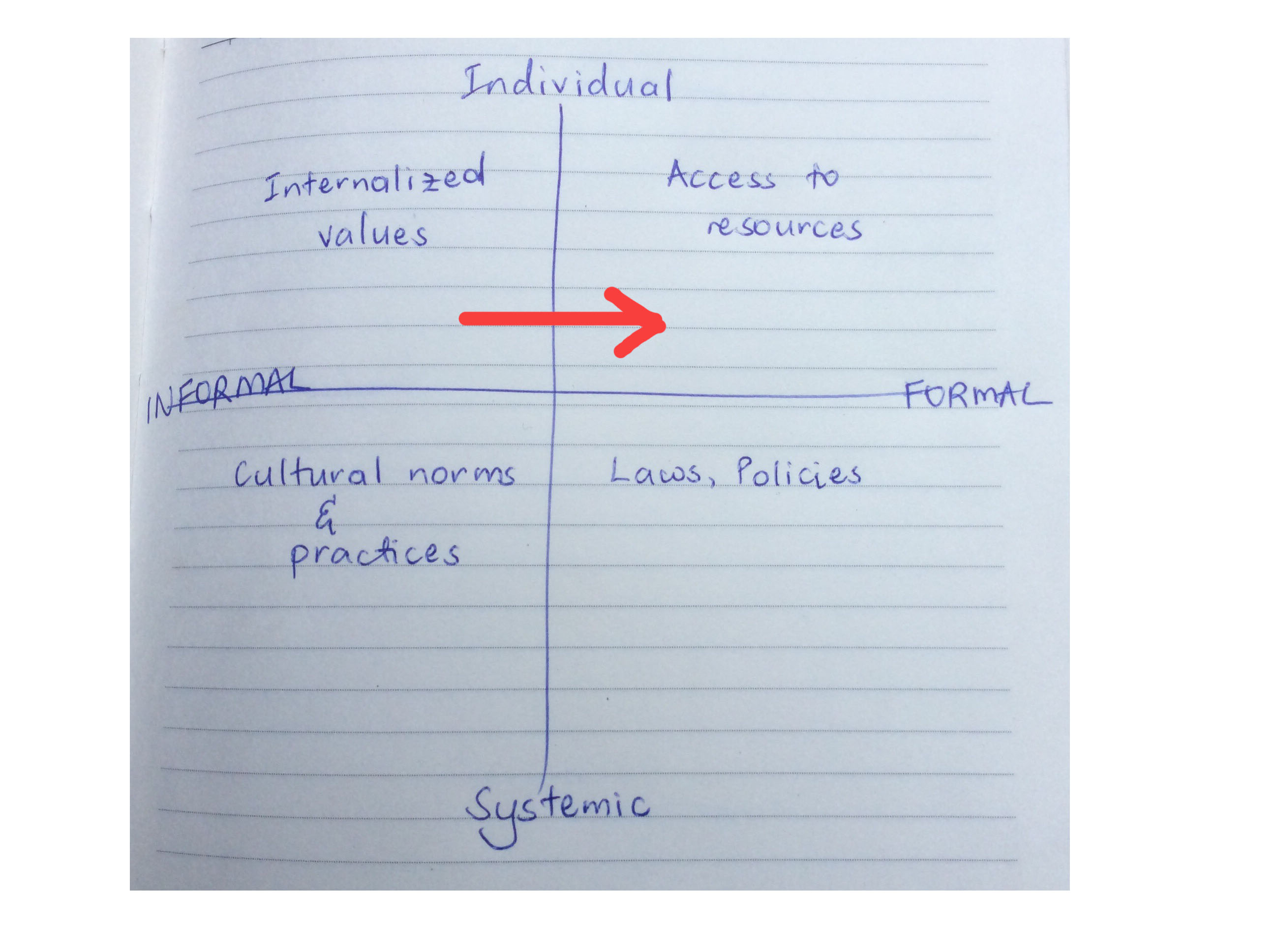

Let’s back up a little and explain this “informal” and “formal”. According to feminist scholar, Dr. Srilatha Batliwala, the formal is where you have systemic processes like laws, policies, resource distribution (in the islands’ case, health centers) and in the informal, we have culture and belief systems. All this interacts on certain levels with the system and the individual.

This kind of advocacy, is a crossing between informal and formal because UDHA was highlighting Article 25 and informing the islanders that they had the right to demand that health centers be constructed. They were creating a force originating from the informal to influence the formal.

While at the registration table, I had to translate questions. Some questions included “have you ever tested for HIV before?”, “has your partner ever tested for HIV before?” and “were you positive or negative?”

“Were you positive or negative?”

How do you say that in Lusoga?

At first, I just looked up and asked the equivalent of “And what were the results?” but I am a stickler for as exact a translation as possible so I kept looking for other translations. The responses I got were “Nga tulibalaamu” for those who had tested negative (that directly translates to “We were alive”) and “Nga tulibalwayire” (“we were sick”) for those who had tested positive. I am ashamed to say that before I caught myself, I actually had started asking the equivalent of “alive or sick?” because it was quicker and that was how the community was responding. But also because when I am not speaking English, I might comfortably say things like that.

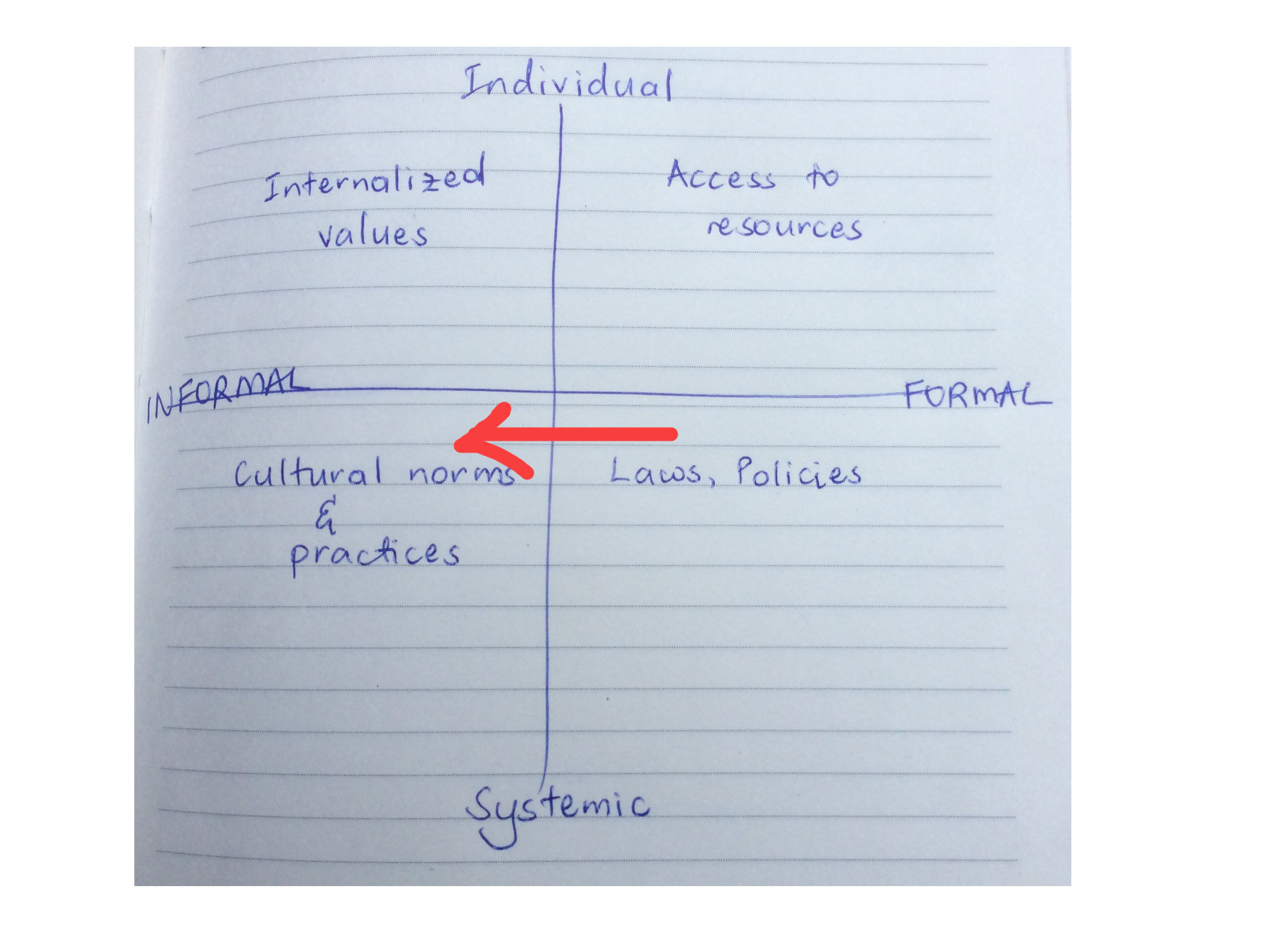

This is not to say that Lusoga or other languages are not sensitive. No. On the contrary, they are extremely sensitive, and if I were to sit down with one of the speakers, I might get a whole range of appropriate translations. However, I am a product of a formal education that ran parallel to my informal life. I studied in English (and was punished for speaking vernacular languages) and returned home to continue living my life in the languages I was punished for in school.

If it creates a force, my education would be influencing the formal/informal divide in a direction opposite to advocacy. I know formal words that explain the other side of the divide, and never learned the words that came from the informal to explain the formal. That’s unfortunately how the world operates. Take the instance of “Article 25”. In 1948, it was most definitely not discussed in Lusoga, and when we went to the island, we took it to the people in English (Some people called it “Akawayiro 25″). The petition was translated as it was circulated, but when eventually presented to the appropriate officers, it will be presented in Uganda’s official language: English.

It is a confusing maze of influences and influencers that I am still trying to figure out and map into the different quads borrowed from Dr. Batliwala. I am happy to say though that while on the island, I eventually started pointing out to the HIV-positive people who said they were “sick and dead” that they looked healthy and alive to me. I also started translating the question to the equivalent of “did you have the virus or not when you tested?”

This was part of my process on the islands, and I am still reflecting on it. I imagine as the islanders signed the petition and heard about Article 25, they each had their own process in navigating their interaction with the formal and informal.