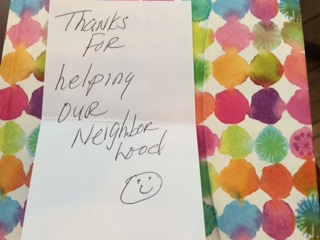

Several weeks ago, my driver’s license fell out of my pocket during a rainy outreach shift with HIPS, a harm reduction organization that works with injection drug users, sex workers, and their communities in Washington, D.C. I assumed that it was lost forever to the storm drains of D.C., until I received a call from my father stating that someone had found my license and sent it to his home with the following note:

Initially, I felt deeply validated by this note. Upon further reflection, I realized that perhaps a more appropriate response would have been to thank this community member for welcoming me into their neighborhood. This incident led me to revisit an internal dialogue I have taken up from time to time while engaging in direct service. In our attempts to “help others” as service providers, can we fall into patterns that do more to make us feel like we’re making a difference, rather than create paths to holistic health and wellbeing for those who lack access to the resources, power, and privileges we already possess?

In posing this question, I can’t help but think about critiques of voluntourism or the Teach For America program. Such programs often emphasize what an individual from outside a given community does for marginalized individuals without recognizing leadership and innovation already present within that space. In a 2012 article for The Atlantic entitled “The White-Savior Industrial Complex” Teju Cole writes, “There is much more to doing good work than “making a difference.”… There is the idea that those who are being helped ought to be consulted over the matters that concern them.” Cole’s words highlight the power dynamics intrinsic to many service provider- client relationships. Service providers often determine the who, what, where, when, and how of an encounter without incorporating the goals or desires of a client. When service provision occurs entirely on the provider’s terms, unforeseen boundaries to access can arise and providers can become gatekeepers despite their best intentions.

With this in mind, I believe it is time to start re-imagining service provision. Instead of treating service provision like an exchange between two entities where one side possesses what the other needs, we can incorporate models that invite collective participation and honor the decision-making processes of everyone involved.

Working at HIPS has offered the opportunity to see new ways of approaching service provision that destabilize the provider-client status quo. One of the ways HIPS does this is by having outreach workers ask people what they “want,” rather than what they “need.” This may seem like a small linguistic tweak, but it can have profound implications for how we think about service provision. Using a term like “need” reinforces a one-way power exchange between a provider and a client, where the client relies on the provider for something they cannot acquire on their own. In this case, the validation one might feel from helping someone “in need,” might also produce feelings of powerlessness or shame for the individual on the other side of that equation. Employing the term “want” acknowledges and values someone’s personal decision-making, shifting control over the outcomes of a service provision encounter from the provider to the individual seeking services. Wanting or desiring something is a universal experience, and using language that evokes this truth creates space to uphold the humanity of both individuals involved in a service provision encounter.

HIPS also encourages its staff and volunteer base to interrogate their own understandings of health and safety as they pertain to the lives of the people who utilize HIPS’ services. Conceptions of health and safety can be extremely situational; police presence might seem to enhance public safety in one neighborhood, but be considered a threat to one’s everyday existence in another. Using heroin might not seem like a health maintenance practice for one individual, but it could be an effective option for someone feeling extremely sick due to withdrawal. While it might feel uncomfortable to hear that someone is engaging in activities that run contrary to what we have been taught constitutes healthy behavior, I would argue that causing discomfort around or alienation from services for a client who feels that their choices are being judged or deemed harmful is far worse. Leaning into the discomfort of difficult conversations has pushed me to be more attentive and creative when it comes to identifying resources and strategies that might work for someone who has different goals and lived experiences than myself.

One of the most valuable models for service provision I’ve seen at HIPS has been its peer educator and secondary syringe exchange programs. Rather than solely hire people with professional public health/social work backgrounds, HIPS strives to include both current and former drug users and sex workers on its staff and volunteer roster. These individuals use their unique skill sets and community knowledge to perform a variety of functions at HIPS, such as running support groups and distributing syringes to people who don’t feel comfortable visiting the mobile services van or office. Instead of viewing service providers as “qualified” by virtue of their education or professional experiences, a peer model acknowledges the value of working with someone who perhaps has shared or similar experiences to a client, offering new opportunities to break down entrenched power dynamics in favor of a more mutual and participatory exchange.

There is nothing wrong with feeling affirmed by working in service provision. However, the intent of this post it to emphasize the importance of thinking critically about how privilege and power function to lift one person in a service provision encounter and not the other, and then identify ways to mitigate the subsequent deleterious effects. I am very grateful that I’ve had the opportunity to start working through my own validation hang-ups and service provision faux-pas this year, and I look forward to continuing this reflective process long after my Global Health Corps fellowship comes to a close.