The concept of global public goods is a traditional way of classifying goods and services based on two factors: 1) rivalrous consumption and 2) excludability. Global public goods are non-rivalrous, meaning their use by one individual does not reduce their availability to others and they are non-excludable meaning people should not be prevented from accessing them. However, exactly which things can be considered global public goods often creates debate. For the purposes of this blog and in line with the mainstream discourse; I define global public goods as goods that benefit all countries, all socio economic groups and all generations. It is from this point, I strongly argue that the drugs required to end AIDS be considered global public goods. I believe the world has an obligation to end AIDS by ensuring that all who require access to lifesaving medications get access to them.

Ending AIDS is both an issue of human rights and social justice. Elimination of AIDS through universal scale-up of testing and treatment will not just protect one group of people or one country or one continent; it will help protect the people on every continent around the world. However, currently only about 1/3 of people who need treatment have access to it. Approximately 12 million of the 35.3 million people estimated to be living with HIV on the planet have access to anti-retroviral medications. More than 21 million people in Africa await HIV treatment.

Why are the drugs not getting to those in need? For starters, issues related to intellectual property rights and international trade barriers have resulted in high HIV drug costs which in turn have restricted people’s access to HIV drugs in poor countries. If AIDS drugs can indeed be considered global public goods, then excluding certain groups of people from them violates the principal of global public goods. For HIV drugs to be truly considered a global public good, all governments have a duty to ensure access to HIV drugs for their people. In low income countries, this raises the issue of whether governments have the right to exercise the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) flexibilities and resist signing of Free Trades Agreements (FTAs) that have a negative effect on HIV programs.

Just recently, through my placement organization, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in Washington, DC; I was witness to two historic AIDS-related events. The first was the replenishment conference for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM). To date, the GFATM has disbursed about $15.5 billion for support of HIV programs and contributed to lowering disease burdens in more than 100 countries. The Fund was replenished by almost US$12 billion for the period covering 2014-16. The second was the bicameral, bipartisan, unanimous reauthorization by the US Congress of the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Stewardship and Oversight Act of 2013. PEPFAR was started a decade ago to help people at risk for and living with HIV/AIDS around the world. The program was reauthorized for another 5 years. Since its inception, PEPFAR has saved and improved millions of lives across the globe. The reauthorization reaffirms the U.S. government’s commitment to fighting HIV/AIDS and improving global health. These two events signalled ongoing global commitment and solidarity behind ending AIDS.

However, if we are to actually end AIDS, more governments around the world still need to do more. African countries, through the Abuja Declaration of 2001, pledged 15% of their budgets towards health. Despite the pledges, only one country has reached that target so far. Of particular note is the number of high HIV burdened countries that are not sufficiently contributing to the end of AIDS by providing universal access to AIDS treatment.

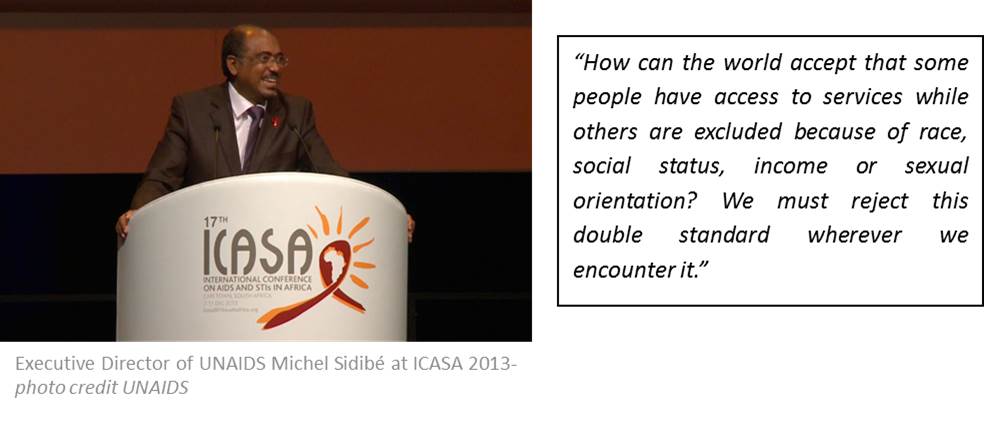

Another critical component of ending AIDS is that interventions have to benefit all socio economic groups. However, currently about 80 countries still criminalize men who have sex with men, while several other countries to criminalise and discriminates people living with HIV/AIDS, people who inject drugs and sex workers. Punitive laws wielded against people living with the virus and those in key populations and the related issues of stigma, discrimination and social exclusion remain as huge barriers to ending AIDS. Removing these barriers is essential to ending AIDS. Protection of human rights for all people is critical to an effective and efficient AIDS response. During 17th International Conference on AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infections in Africa (ICASA), in Cape Town South Africa, December 2013, UNAIDS’ Executive Director Michel Sidibé asked:

In January I attended UNAIDS’ Post-2015 Agenda, high level roundtable discussion. One of the key objectives was to offer input to the group developing the UNAIDS-Lancet Commission: Defeating AIDS – Advancing Global Health on how the experience of global HIV/AIDS programs, particularly efforts to ensure equitable access to healthcare for key populations can help inform and improve global health approaches in the post-2015 period. This is part of UNAIDS’ effort to eliminate stigma and discrimination against people living with and affected by HIV through promotion of laws and policies that ensure the full realization of all human rights and fundamental freedom. It was clear from this high level discussion that we can’t end AIDS if we are not willing to address the needs of key populations and that is more likely to happen if the voices of marginalized people are heard.

Everyone will benefit from the end of AIDS; therefore, all nations have an obligation to ensure universal access to AIDS drugs for all their people regardless of social, cultural political, economic or religious differences. Ending AIDS requires that universal access to treatment of AIDS be a global public good.