Before joining Global Health Corps, I worked for two years in Washington, D.C. as a strategy consultant. In my role, I evaluated market conditions for business and product development and supported the formation of M&A strategies. In doing so, I brainstormed ideas, constructed models, drafted documents, and delivered presentations to clients. After delivering the final presentation, our work was largely done; it was up to the client to evaluate and operationalize our recommendations. For the most part, we were not involved in questions of implementation.

Two months ago, I started my Global Health Corps fellowship as an HIV Systems Coordinator with Clinton Health Access Initiative in Kampala, Uganda. In many ways, my consulting background has positioned me well for the role. However, my lack of experience in implementation has admittedly proven challenging.

Soon after beginning my fellowship, I learned firsthand an oft-mentioned aspect about this work: perceptions from the center rarely match the realities in the field.

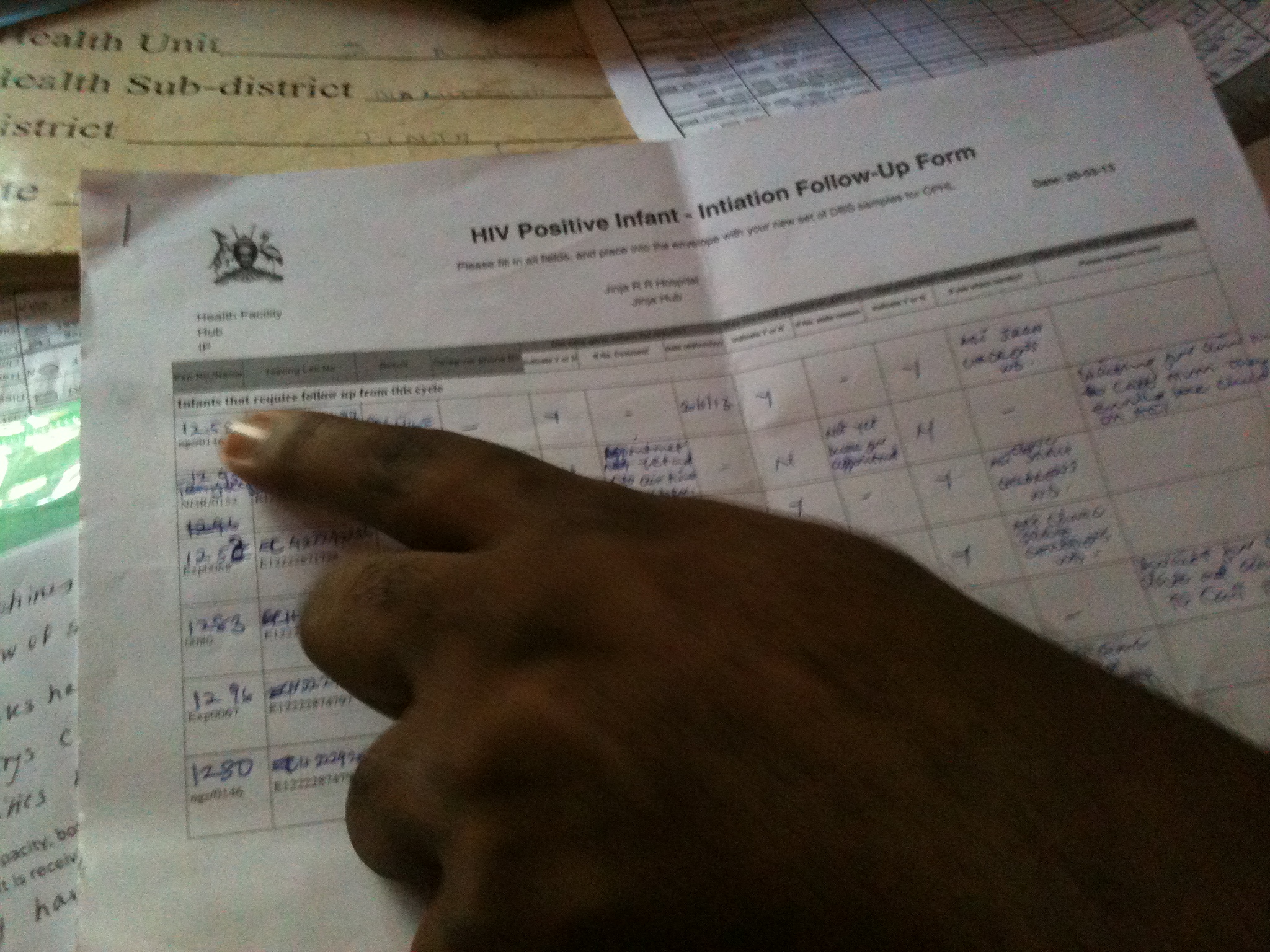

Currently, Uganda is rolling out a number of patient tracking and retention tools for the diagnosis and treatment of HIV positive infants. One of these interventions—the use of HIV Positive Infant Follow-Up Forms—promises to strengthen linkages between diagnosis and treatment initiation for HIV positive infants. The follow-up forms were piloted across a number of sites last spring and are in the process of being scaled nationally.

During my first field visit, I learned that despite previous training efforts, the majority of facility staff members were not familiar with the purpose of the HIV Positive Infant Follow-Up Forms. Only one facility recalled even receiving several forms as a part of the pilot program last spring.

These findings reflected multiple challenges: the follow-up forms were not being sent out regularly, and even pilot sites had stopped receiving forms some months ago. During the pilot, forms that had been sent did not always convey the correct patient test records for facilities to use in following up with caregivers. Lastly, training efforts had not yet scaled across facilities or convincingly demonstrated the purpose of the follow-up forms.

New as I am to implementation, this experience has provided me with a number of critical insights that will guide my work for the remainder of the year.

- Implementation demands constant coordination. And, much to my chagrin as an avid iPhone user, email alone will not suffice. Frequent phone calls and in-person meetings, as well as follow-up, are necessary to move projects forward.

- When faced with a complex challenge, break it into its component parts.

- Identify challenges stemming from the center. Solve these first. Challenges in the field will persist if central-level operations are still not running smoothly.

- Learn how to prioritize: not everything can be done at once.

- Entering the implementation phase of a project while it is already underway is challenging. Communication with all stakeholders to gain a full understanding of the project, as well as in-person observation, is critical in this phase.

As I continue on, I am sure these five lessons will be just the start of my learning process. Challenging as this phase may be, I am looking forward to the end goal—improving care for HIV positive infants across Uganda.