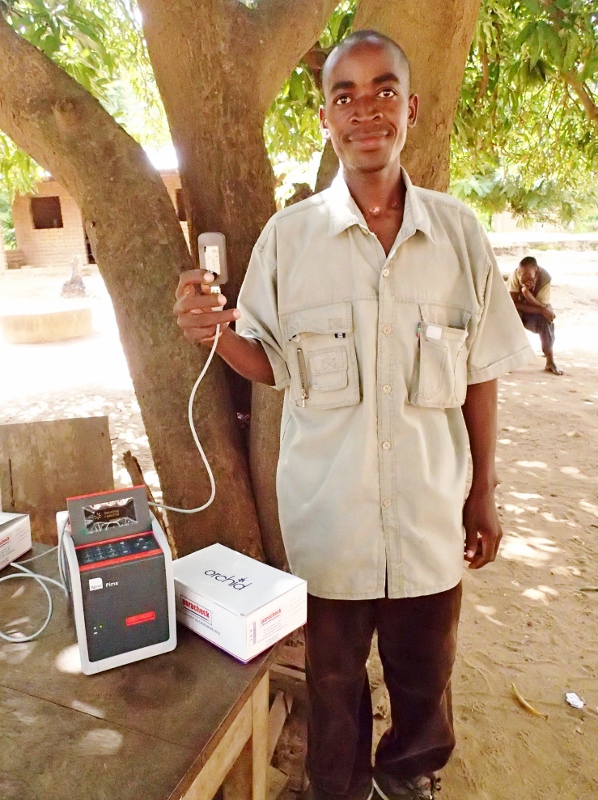

In the second half of my fellowship, I have a completely new project on my hands: supporting the use of a point-of-care CD4 diagnostic, the Alere Pima CD4 Analyzer. There are currently about 120 Pimas in-country and most of these are set up with USB modems and mobile network SIM cards that enable them to automatically transmit results to the Ministry of Health in Lilongwe, every day after testing. I kicked off this project for myself with a 7-day field trip the other week that had me driving around 6 districts in Southern Malawi, armed with boxes of modems, envelopes chock full of SIM cards and my notebook, to help troubleshoot instruments incapable of easily completing this essential reporting task.

I just said a lot, so let me try to zoom out a bit.

Malawi has the 9th highest prevalence of HIV in the world, with 10.8% of the population currently living with the disease (CIA World Fact Book). This adds up to an estimated 1.1 million people. Which is a lot. Malawi is considered a resource limited country, and, as such, not every patient who tests positive for HIV is able to start ART treatment right away. Malawi does cover 69% of advanced HIV infections with ART (WHO, 2012), which isn’t too bad compared to other top-ten HIV prevalence countries. It does, however, still leave a lot of people without treatment and it’s a far cry from what Botswana and Namibia, as peer countries on this aspect, have achieved.

In addition to this, it’s also widely known that a high proportion of patients who receive a positive HIV diagnosis are not able to receive the follow-up tests they need to help them initiate treatment, monitor disease progression, and measure treatment efficacy, particularly in rural sites or other settings with limited diagnostics infrastructure (Malawi Point-of-Care Implementation Guidelines). This is where point-of-care (POC) comes into play. POC is a vocab word in this biz that, in one sense, means the whole diagnostic process—from collecting the patient sample to running the test to getting back the result—can all be done in one day, literally in front of the patient.

This sounds like it should be a straight forward solution, right? Yes and no.

Yes, it’s straight forward, on one hand. In the non-point-of-care scenario—very much the default, until recently—either the sample or the patient is obliged to travel to a laboratory, e.g. the district hospital. These, however, could be as far as 60 kilometers away and few people own vehicles or have access to public transport. At minimum, this adds days to turnaround times for test results and therefore requires patients to come back again to their local health center for care based on the diagnostic outcome. This is a problem for people who not only don’t live very close to their local health center, but who are also just plain busy, like all of us. Follow-up trips on top of follow-up trips to the health centers take time away from work, cooking and child care, and cost money. This is not ideal.

No, it’s not terribly straight forward. For POC devices to work in this resource limited context—and by “work” I mean function reliably across the whole nation, for years—they have to be designed very intelligently. The health care workers using them don’t have as much training as they would like, the health clinics in which they’ll live don’t have temperature controls or reliable electricity, and the supply chain to bring consumables and reagents is plagued by bad roads and broken-down vehicles. It’s not a trivial matter for a company like Alere to develop a diagnostic robust enough to succeed at scale in this setting. Oh, yeah, they also need to be inexpensive, so that deploying them to a hundred health facilities at a time can be feasible in the first place.

Not so straight forward.

But, boy, once they work, the potential for impact is enormous.

If all goes to plan, POC devices can significantly mitigate the need for costly and logistically difficult sample transport, absorb workload from over-burdened laboratory technicians, reduce patient loss-to-follow-up, and—perhaps most important—enable health workers to make treatment decisions faster.

Enter point-of-care CD4 diagnostics!

At the behest of the Ministry of Health, which has guidelines outlining how POC and CD4 diagnostics should be done, CHAI is helping to ensure that those guidelines are actually followed and that end-users in even the smallest health facilities in the remotest parts of the furthest districts have what they need to do so.

Bottom line is if everyone can’t start ART treatment immediately, smart prioritization is needed. The concentration of CD4 cells in the blood of an HIV-positive patient is one way to identify a patient in need of quick treatment, as per the Malawi MOH and WHO guidelines. This project seeks to close the gap between CD4 testing availability and ART availability. Whereas, previously, a patient could be literally walking around a health center stocked with ART and simply not know that they are eligible for treatment, now disease progression based on CD4 can be monitored with the Pima, allowing patients to initiate within days of being eligible.

With so many people in this country suffering from HIV/AIDS, directly or indirectly, this feels like a very worthwhile thing to be doing.