When typing an email, we expect with a great deal of certainty that our thoughts will translate to words on the screen through the movement of our fingers across a keyboard. The pressing of a finger on a key is the output of a highly efficient process whose origins can be traced through the body and brain. Evolution fine-tunes neuronal processes to produce highly specific motions, like manual dexterity, in humans. Evolution is interested in operational efficiency.

Neuroscience, the interdisciplinary study of the nervous system, outlines the operational efficiency the body employs. It allows us to examine how, at the neuronal level, a microscopic proceeding can offer insights into a macroscopic process, for example, an internal office procedure. Consider in parallel the corticospinal pathway, a network of neurons responsible for the voluntary movement of fingers, and the request for the purchase of Post-it® notes, a standard office supply. The procurement of Post-its and the movement of a finger have surprising similarities.

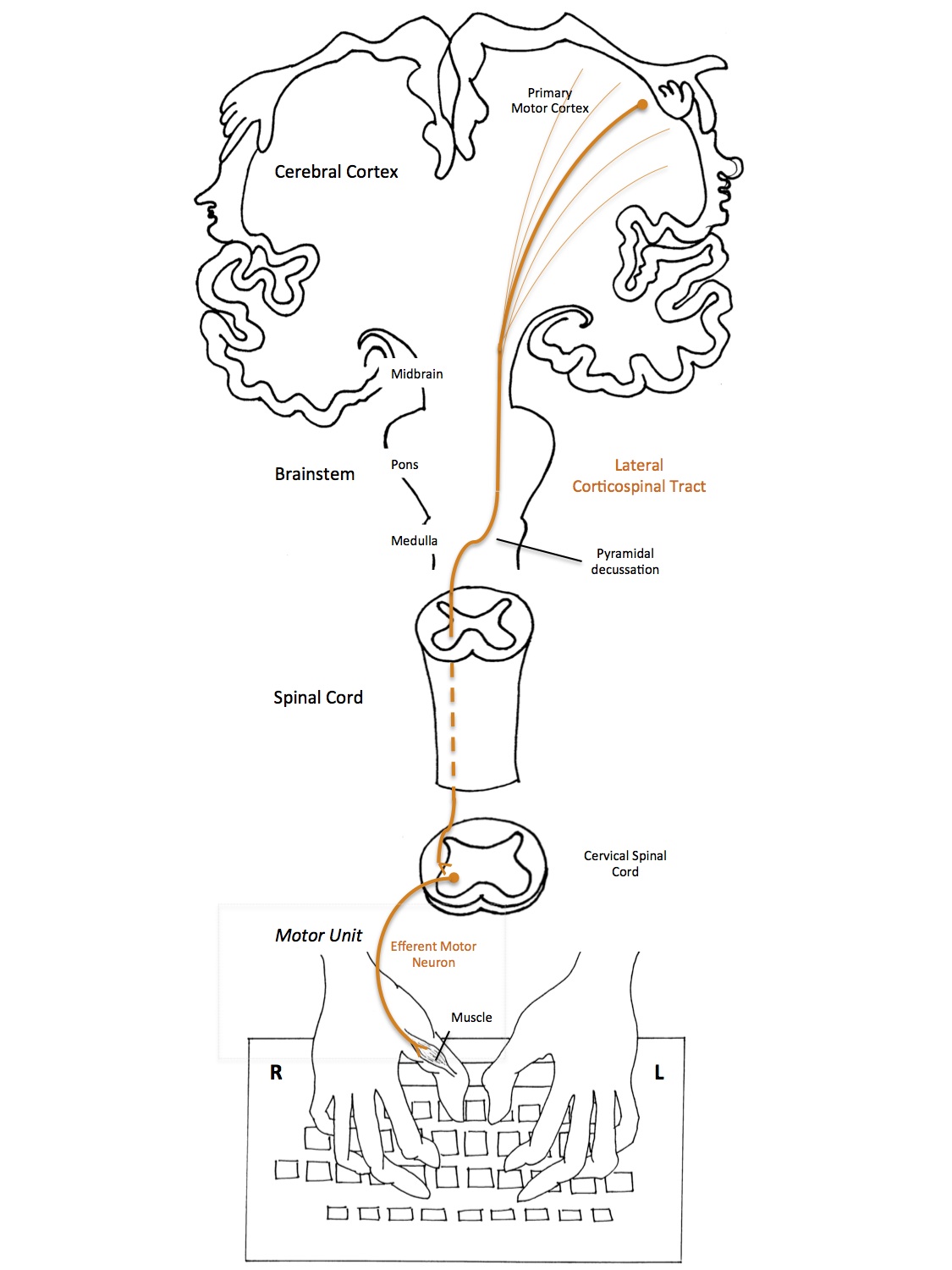

If this proposition leaves you scratching your head, you’re starting in the right place. Beneath the site of a stereotypic scratch of confusion is the primary motor area of the cerebral cortex. Once stimulated, the primary motor cortex issues a request for a highly specific, voluntary movement, like the tap of a finger on a key. From the motor cortex, the request begins its descent through the body in the form of an axon.

In the office, the procurement of Post-its begins with the need for an attractively colored, appropriately adhesive, rectangle allocated for incomplete thoughts. When considering potential productivity-enhancers, employees, much like the motor cortex, call the shots; they set the agenda then communicate the request to the department responsible for procurement, referred to henceforward as the “Procurement Department.”

The axon, derived from the motor cortex, passes through the brain and brainstem before descending through the spinal cord in pursuit of imparting movement. The axon and its subsidiaries form a traceable pathway known as the corticospinal – “from cortex to spine” – tract. Along this path, they gather and integrate information from other brain structures. These feedback loops fine-tune the command to ensure the desired movement is executed with precision and proper intensity.

Similarly, collaboration among employees streamlines the specifications, quantities, and timelines of item they request: should the Post-its be pink, purple, or polka doted? Are two or two hundred needed today or next Tuesday? Clear and concise communication is essential since neither the primary motor cortex nor employees directly impart the action they request, both use middlemen. The corticospinal pathway descends on the motor unit: the final efferent neuron and the muscle it seeks to contract. Employees depend on the Procurement Department to deliver stacks of Post-its.

Reaching these middlemen requires the operational pathway to literally or figuratively cross a “line,” properly positioning it to transfer its message. In the body, interior to the nape of the neck sits the medulla oblongata, a bulbar structure at the base of the brainstem that straddles the body’s midline. Just prior to entering the spinal cord, the axons of the corticospinal tract cross the midline of the body in the medulla. Consequently, the left side of the brain controls the movement of the right (opposite) side of the body. If the intent is to find “JKL;” on the keyboard, the axon is now positioned properly.

About halfway down the neck, at the cervical level of the spinal cord, the corticospinal tract synapses on the motor unit. The message that originated in the motor cortex juts out laterally, down the length of the arm, and into the hand where it acts on its final target, the muscle. [Right thumb hits the space bar.]

Just as the final motor neuron cannot fire until it is fired on, the Procurement Department can’t carry out a request until it receives one. To accomplish this final task, the employees must bridge the physical or theoretical divide – perhaps a hallway or email account – that separates line from operations staff. Once Procurement receives the request, it is poised to solicit suppliers. Post-its are on their way.

Fortunately for the obsessive office organizer, repeat requests will generate a more consistent supply of Post-it notes; repetition strengthens systems. A typist’s skills are an unintended consequence of antiquated neuronal processes. The more times the motion – typing – is processed in the body, the more coordinated the response of neurons becomes, and the more accurate the fall of fingers on intended keys will be. Muscle memory – motor learning – is, in the body, what decades of supply chain professionals have hoped to be for business.